Poor Recipe

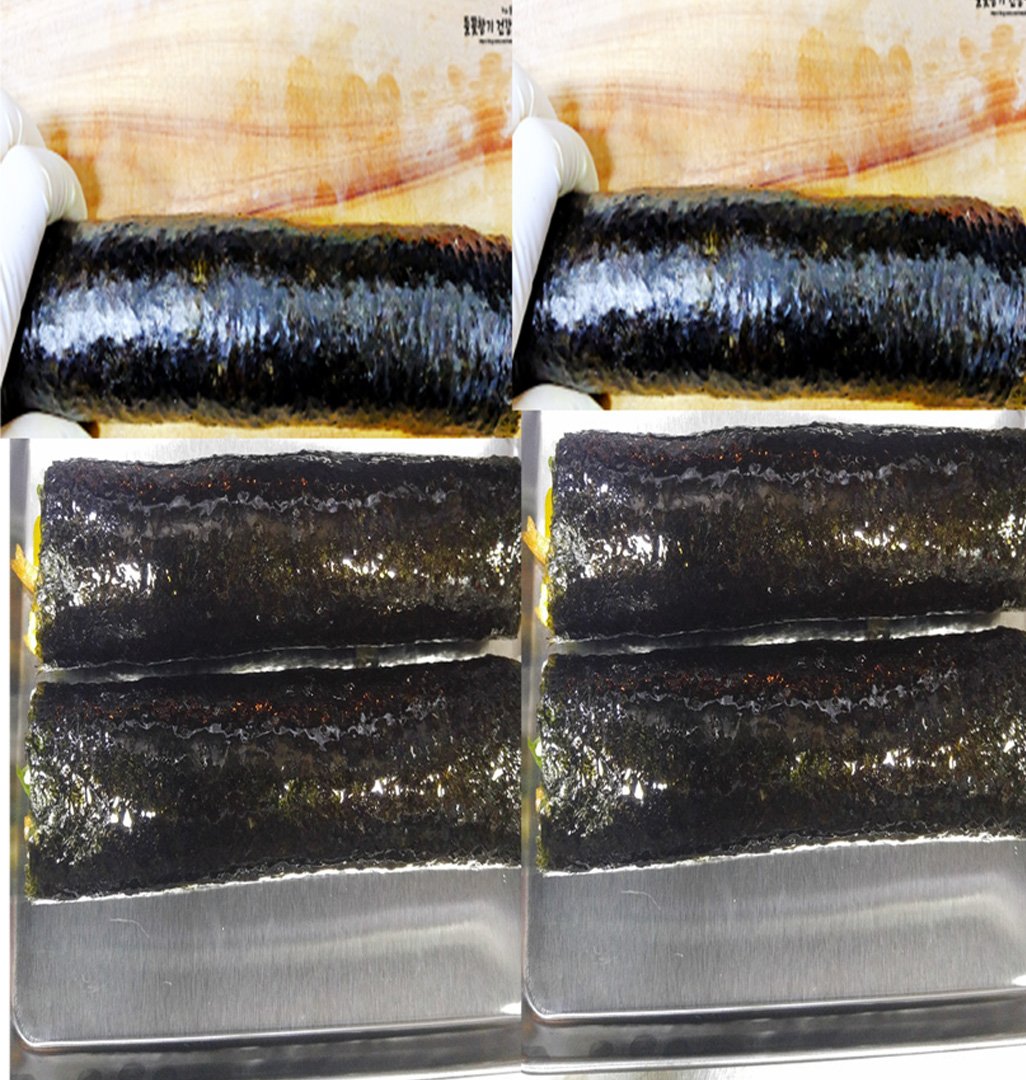

This is more than just an image of food. It is Gimbab I-Ching. When I was working as a teaching assistant at RCA last summer, one of my tutors told me she often bakes shortbread, and the process always reminds her of home. I understood exactly what she meant—not just the physical space, but a deeper, generational union. A sense of belonging that isn’t tied to geography. Home, for me, is a feeling—something long gone, yet present in the rituals of my body. When I cook, I’m connected not only to my mother, but to my grandmother, and her mother before her. Without needing a real, physical place, this 만남의 장—a space of encounter—comes alive through food, and even more through the act of cooking itself. I eat black gim with white rice. Sometimes I add a bit of kimchi. But that’s not the point. What matters is the process. As I prepare and eat it, I’m instantly brought back to fourth grade—to a school field trip where my mom had packed her precious gimbab. Some kids brought premade rolls from a restaurant, but I remember the difference. Hers was full of care, full of love. But even that gimbab now exists only as a transformed version—one among the ten thousand recipes found on 10,000 Recipes (a popular Korean recipe platform). It is a chosen variation among countless others, altered through time and digital circulation. Through these recipes, I reconnect with my mother’s emotion and the feeling of my hometown—yet simultaneously, I lose something. In creating Gimbab Geon-Gon-Gam-Ri, I was influenced by Hito Steyerl’s essay In Defense of the Poor Image. The gimbab photographs I collected—low-resolution recipe snapshots taken by anonymous individuals—embody what she calls “poor images”: compressed, circulated, often degraded, yet imbued with emotional density and everyday labor. These images may lack clarity, but they carry memory, care, and cultural transmission. Through layering and rearranging these poor images, I created a digital landscape of trigrams—each slice of gimbab acting as a visual cipher for Geon (☰), Gon (☷), Gam (☵), and Ri (☲). Like the I-Ching itself, they form a system of meaning that arises not from perfection, but from transformation, repetition, and imperfection. In this work, digital images serve both as traces and as ruptures. They are echoes of something once tactile and intimate—an act of love wrapped in seaweed and rice—but now filtered through the algorithms of online platforms, compressed into JPEGs, and stored in recipe blogs. While these poor images make the memory accessible, they also flatten it. The warmth of my mother’s hand, the texture of still-warm rice, the scent of sesame oil—all of it becomes distant, pixelated. And yet, this very gap—between what was felt and what is seen—becomes fertile ground for reimagining. The Gimbab, reassembled into trigrams, resists erasure by transforming. It does not mourn the loss of the original, but instead constructs a new field of meaning—a new language of care, migration, labor, and lineage—through the debris of the everyday.

Gimbab Geon-Gon-Gam-Ri, Digital Image, 2025

A while ago, I baked shortbread made me think of my tutors