Sugar Sugar Rune

In 2018, I began to sense that contemporary love ideology was becoming highly commoditised. I started drawing heart emojis, and one day during a phone call with a close friend, the topic of the Japanese manga ‘Sugar Sugar Rune’ came up. My friend (@ahnnewjin), a fellow BFA graduate and such a talented creative art historian who actually paints, and I was talking to her why I had drawn to making heart-shaped origami out of the blue - even though I was origami geek when I was a child. We began to question what love meant to us, especially as those who remembered the pre-internet era, and how that meaning had evolved over time.

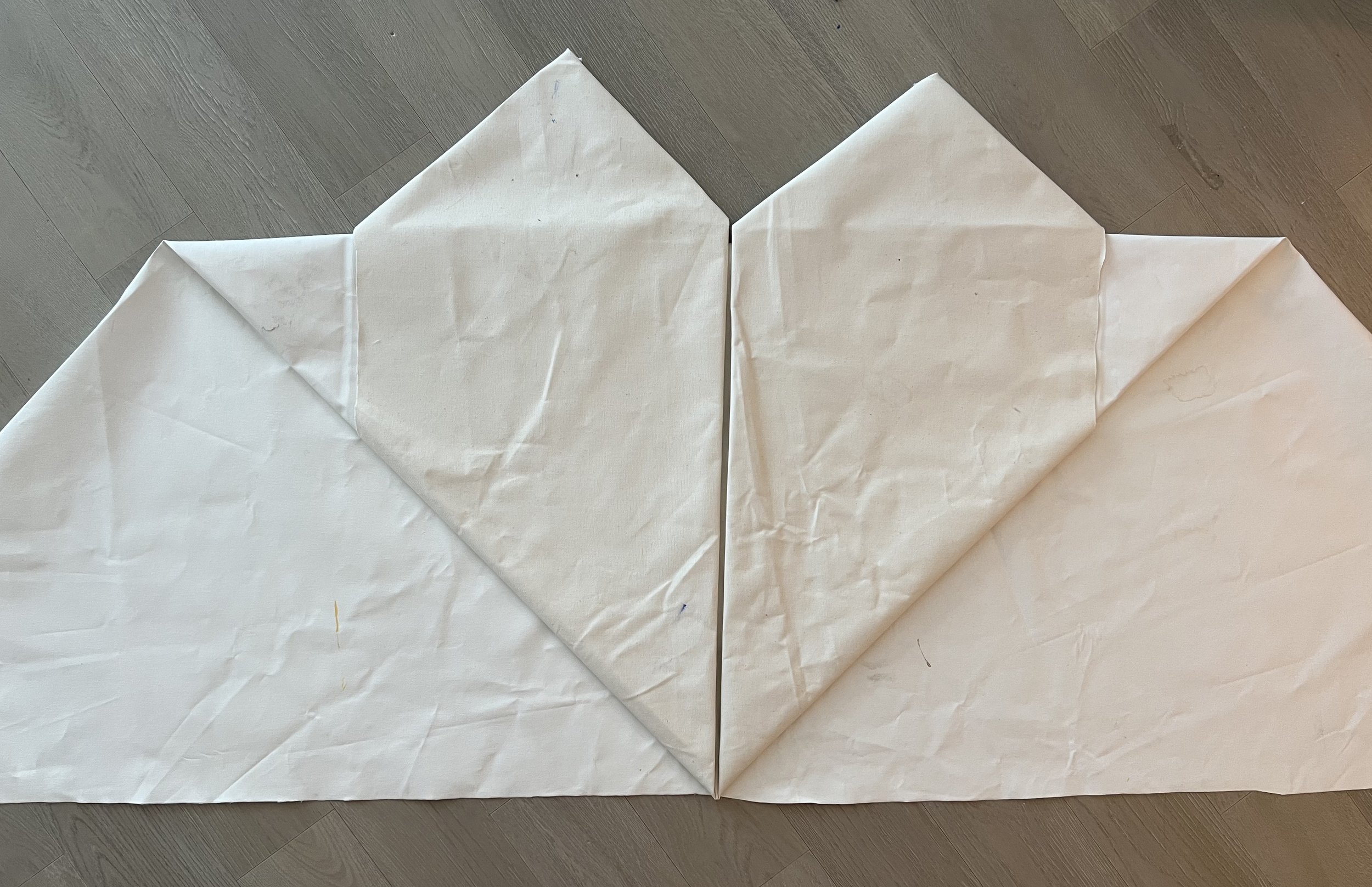

(I also did fold up my canvas to make heart-shaped origami too)

The Representation of Love in Anime

We recalled all the Japanese animations - Full Moon (満月をさがして), Magic Knight Rayearth (魔法騎士レイアース), Magical DoReMi (おジャ魔女どれみ), Inuyasha (犬夜叉), Cardcaptor Sakura (カードキャプターさくら), Sailor Moon (美少女戦士セーラームーン), Wedding Peach (愛天使伝説ウェディングピーチ) - we had been captivated by as young girls, questioning what love had looked like back then and how it had changed over the years. The female protagonists in these animations often embodied moral values, helping others as princesses or sorceresses, yet they still faced tragic and unfulfilled loves, often losing themselves in these conflicts. These characters became objectified yet were expected to embody multiple roles simultaneously.

As part of the generation of Koreans born in the '90s, we grew up watching these portrayals of love. I began to obsessively collect heart images from these animations, which presented love in the form of soft, jewel-like shapes. Yet, in many of these stories, there is always a dark antagonist—a black heart, which is portrayed as even more powerful than any other heart. (Sugar Sugar Rune presents love as a magical spell and monetary unit divided by colors and prices. Each color symbolizes a different meaning and value of love, creating a layered portrayal of love's commodification.)

These are the original heart images from Sugar Sugar Rune including meanings and price

Data-driven Images of Love

Using Python and OpenCV, I visualized the RGB values of each collected heart image, creating abstract, data-driven representations of hearts with unique and subjective meanings. These hearts, while initially possessing different colors and meanings of love, were reduced to patterns of numerical data, symbolizing the irony that modern love ideology often reduces emotions to mere symbols or images without substance. It raised the question: are we truly experiencing love, or merely consuming its commodified symbols?

The Collision of Love and Society for Korean Women

As I grew older, I found that my understanding of love was evolving, yet many women, myself included, struggled to break free from the ideologies surrounding it. I experienced the impact of these societal constructs firsthand through my first marriage, encountering the intense expectations and limitations that Korean women face. Women who openly confront their realities or question societal norms are often stigmatized as mentally unwell. This societal “witch hunt” persists even in 2024, silencing countless women who decide that remaining quiet is the only way to avoid being labeled as “crazy.”

In Korea, these accusations often take the form of weaponized mental health diagnoses. Right before and after my divorce, exactly four men told me that I “had a mental illness.” One of them, perhaps predictably, insisted that I get tested for OCD, which led me to visit a psychoanalyst. Of course, two psychiatrists later confirmed that these accusations were nothing more than a form of manipulation. This experience taught me that confronting uncomfortable truths often provokes fear in others. As someone who speaks what I see, plainly and without restraint, I inevitably ask questions that are sharp and bold. But for those who cannot face the truth, the easiest way to extinguish the flame of such questions is to discredit the questioner. “You’re mentally ill,” they say, attempting to erase both the question and its source.

Asian women, in particular, are acutely vulnerable to this. Societal expectations—both in Korea and abroad—often push us into silence, forcing us to conform rather than risk being labeled “mad.” These pressures are compounded by the racial and gender stereotypes we face in Western contexts, where hypersexualization and assumptions about submission create an additional layer of discrimination.

But I refuse to hide or feel ashamed of my reality simply because it may seem distant from the norm. To question one’s reality, even when it diverges from societal norms, is perhaps one of the most fundamental human tasks. I embrace this divergence because it holds significance. I am an extraordinary person in Korean society, and while I know there are others who pursue such a path, I also recognize the pain it can bring. Yet this pain is not without value—it is part of the ongoing struggle to define ourselves beyond societal limitations.

Conclusion

Through this journey, grappling with love and societal expectations, I have come to a deeper understanding of love and its evolving nature in modern society. Though love may constantly change, the questions it raises remain persistent. What is love, and how should it be defined?

Contemporary love may be more than a commodified image—it may be a value we must continuously reclaim, redefine, and protect, even in the face of discomfort and resistance.

Sugar Sugar Rune, 2022, Open CV