feed me not

‘체하다’는 영어 표현은 없다. 지금처럼 지독한 소화불량에 시달려야하는 때가 또 있을까. 오장육부의 움직임이 정지한 것 같은 그런 상태 말고, 지금 이 순간, 한국 사람이라면 심리적으로 ‘체한’상태이지 않은 사람이 얼마나 있을까?

20대엔 섭식장애로 시달렸다. 그리고 이십대 후반이 되어서야 몸과 친해졌다. 가까운 친구와 통화할 때면 “서른이 되서야 제대로 눈 뜨고 사는 것 같다”라고 말한다. 위장병과 멀어졌다고는 하지만 직접 겪은 바가 있으니 누군가 소화불량으로 시달릴때면 종종 그 출구없음에 공감할 수 있다. 어릴땐 할머니가 손가락 끝을 바늘로 따줬지만, 그런 민간요법의 시각적 효과만큼 빠른 진통제는 이제 나한테 없다. 최근 10대 여자 청소년 거식증 환자는 97% 증가했고 폭식증, 거식증 등 식이장애를 앓고 있는 환자는 10명 중 8명 가량이 여성이다. 나조차도 10대부터 극단적인 식이절제, 식이요법 후 폭식을 반복하기를 10년, 매일같이 위장약을 달고살았다. 굳이 섭식장애라는 무서운 단어를 쓰지 않고도 꽤나 많은 사람들이 거식증이나 폭식증에 시달리고 있음을 인식하고있다. 그렇담 먹는 것과의 전쟁은 끝났는데, 심리적으로 체한 상태로 지속된 영원한 휴전상황은 어떻게 설명할 수 있을까.

외국에서의 소화불량은 한국에서의 체한 증상의 그 심리적 상태를 동반하지 않는다.

Bloated feeling or Upset stomach or Nausea or Indigestion 그 어떤것도 체했다는 표현을 담을 수가 없다. 왜냐하면 막힘의 물리적 감각은 심리적 정체와 맞닿아있기 때문이다. ‘체(滯) + 하다’의 滯는 막힐 체, 머무를 체로 지체하다의 체와 같은 단어이다.

반대로 ‘feeding’은 한국어로 온전히 표현할 수 없는 영어 단어이다. 밥먹는 콩순이는 입에 구멍이 나있다. 솜으로 된 몸 안에는 소화시킬 수 있는 그 어떤 장기도 없지만 혼자만 쓰는 변기도 가지고 있었다. 콩순이에겐 내가 먹던 과자며 밥이며 모두 우겨넣어줬다. 그렇게 콩순이에게 밥을 ‘먹여준다’고 생각했다. 여성이 ‘먹는 것’ 그리고 ‘먹이는 것’과 긍정적인 관계를 형성하기 어려운 것은 결국 한국어 단어로 ‘먹이’거나 ‘먹여주기’를 이해할 때, 그 행위에 자기 자신이 내포되기 때문이 아닐까? 애초 모유수유를 할 수 있게 생물학적으로 진화한 사실을 알게된 여성이, 여성이기 이전에 한 인간으로서 자기 자신을 feeding한다는 인식, 곧 스스로를 돌보는 경험, 관계를 형성하기도 전에 먼저 다른 누군가를 먼저 먹여주는 경험을 더 중요한 감각으로 형성하도록 교육받지 않았던가? 또는 반대로 먹는 것을 절제함으로서 인정받는 경험을 가지지 않았던가?

이창동 감독의 영화 시에서 주인공 미자는 손자에게 묻는다.

“할머니가 제일 좋아하는게 뭐라그랬지?”

“내가 밥 많이 먹는거”

하지만 한강의 채식주의자에서 영혜는 먹기를 강요당한다.

이 두 캐릭터의의 차이점이 무엇이었을까.

영화와 책을 동시에 같이 본건 우연이지만 우연에따라 읽게되고 보게되고 듣게되는 모든 예술 형식들은 내가 그리는 그림과 마치 누군가 지켜보며 나에게 던져주는 것 처럼 항상 그들끼리 맞닿아있다. 나는 이럴 때 우연을 넘는 감각을 느낀다. 장난스럽게 말하자면, ‘신이 왔다’고. (그렇기 때문에 메를로퐁티의 ‘보는 것’ 대한 철학적 논증은 신비주의적으로 들리지만 시각 예술을 하는 사람들이라면 이해할 수 있는 어떤 지점을 말하고 있는 것이 분명하다.) 지난주 Criterion 계정에 에 우연히 뜬 이창동 감독의 영화 ‘시’를 보고, 한강의 ‘채식주의자’ 영어 번역본을 동네 책방에서 마주치고 사게된 일, 책을 읽으며 한국적 표현과 영어적 표현의 언어적 다름을 문학적으로 인식하는 과정, 한국의 정치적 상황을 지켜보다 갑자기 알게된 팔레스타인 저널리스트의 부고 피드, 잔뜩 체한기를 가라앉혀주던 할머니의 손길, 그리고 사랑을 표현하는 방법은 지독하게도 먹이는 것 밖에 모르는 나의 외로운 엄마의 사랑 방식이 어떻게 우연처럼 동시다발적으로 한 순간 출연했으며 그 모든 것의 시각적 연상은 어떻게 입에 연결된 내장기관이 없는 콩순이의 구멍난 입술로 귀결되었을까. 이 생각을 하고있던 찰나 Polo & Pan의 Cadenza를 듣고있었다. Cadenza, 반복되는 가장 단순한 멜로디의 계속되는 변형은 이 지속된 연속의 경험, 지연의 경험을 상기시키면서 지금 나의 경험이 절대 한 개인이나 시대의 것이 아닌 반복된 연속적 공통된 경험이라는 것을 일깨워준다.

Feed는 고대 영어 fēdan 에서 유래했다. to nourish, to give food to, to foster의 뜻을 가진다. 즉 feeding은 단순히 먹이는 행위가 아니다. 살게 하는 손, 자라게 하는 마음, 기운을 덜어주는 행위이다. Feeding 을 한국어로 번역하면 먹이다라는 뜻으로 너무 기계적이고, 수유하다는 생물학적 여성에게만 한정된다. 먹여주다의 한국말도 ‘주다’에 초점이 맞추어지기 때문에 돌봄과 사랑이 약화된다. ‘기르다’는 식물, 아이, 동물로 대상이 제한되며 노동, 감정, 생존이 합쳐진 개념이 만들어지지 않는다.

팔레스타인 전쟁의 폭력을 있는 그대로 전달하던 Hossam Shabat이 며칠전 세상을 떠났다. 그의 폭력에 맞서는 위대함과 용기는 사진만 봐도 바들바들 떨리는 내 몸을 몇번이고 감싸안았다. 그의 용기가 어떤 질문을 하게했다.

“내가 세상을 위해서 가장 작은 실천적 salvation을 지금 이 순간 할 수 있다면 그건 무엇일까.”그러자 내 안에서 아주 조용한 목소리가 들렸다.

“누군가를 먹이는 것.”

체기가 도저히 가시지도 않는 마당에 누군가를 먹인다는 것이 가능한일이기나 할까. 누군가를 먹여살리기 이전에 나 자신을 먼저 보호하고 양육할 수 있어야하지 않을까. 그런데 지금 이 순간에도 세상은 끊임없이 Feeding하려는 욕구만 넘쳐나는걸 보면, 우리가 더이상 feeding하고도 만족할 수 없는 세상에 살게된 것 아닐까. 디지털 feeding(돌봄)이 과잉섭취되면서 소비되어버린 이미지는, 이제 소화불량에 시달릴 수밖에 없는 — 체할 수밖에 없는 위치에 놓여 있다. 물론 이 모든 것엔 현재 한국에서 일어나는 지연의 경험이 맞닿아있으며 그렇기 때문에 절대 개인적인 경험일 수 없다.

A Puker

A Puker (토하는 사람)

I can only describe my facial expression nowadays as one that can only be imagined as a “puking” face.

I drew the person who is puking, and this is not the first time I’ve drawn this figure. It emerged for the first time in 2017. Back then, I was disgusted not only by the physical violence I encountered but by the silent, innate nature of violence in Korea. It was right after the Gangnam Station incident, the Me Too movement, and the continual sexual harassment and violence at academia, including cases of drug-assisted rape by Korean celebrity. I had to enclose this constant trauma within myself, forcing a detachment from it in order to make my life better and to take myself not so seriously (it was too painful to face back then, and still I am)

Now, I face this again. It is 2024 and things didn’t chance much. I think it is much horrific now. We are witnessing genocide every day. How casually we use such heavy, light words now—unreasonable death. Death that people treat as just another story yet it is reality.

I draw the person who vomits, Puker. Literally, it is the person who vomits—who spits out. It is a bodily association with particular symbols. This act of vomiting is such an expression of meaninglessness and the absurdity of life, serving as a metaphor for existential angst.

The fundamental human emotion that signals danger and the violation of bodily boundaries has been violated itself. The aversion to vomit, once a marker of disgust, now intersects with deeper psychological boundaries—the boundary between what is "inside" versus "outside" ourselves. The act of vomiting becomes not only a bodily function but an existential act: the body expelling the unbearable, the unspeakable, the uncontainable.

This is what it feels like to live in a world where violence has become so normalized that it is no longer even shocking. What is left for us, then, but to expel it? To vomit it out, to purge it, and yet, the act of purging itself feels futile. The violence is internalized, festering within us, and the boundary between inside and outside becomes ever more blurred.

In the end, this vomit is not just an expulsion of matter. It is a desperate act of self-preservation—a way to rid the body of the contamination of a world gone numb to its own suffering.

Beyond Boundaries: Thoughts on Vertical and Horizontal Gaze in Painting

〰️

〰️

The concept of a horizontal gaze has taken on new relevance for me in recent years, especially after moving to London in 2023 and now living in the US. This shift in geography has not only introduced a new language—English—but also a new way of seeing. I vividly remember gazing at the horizon in a park here. The horizon appeared vast, even, and fine, which struck me as profoundly different from the landscapes I am familiar with in Korea. Korean landscapes are shaped by mountains, and the view often leads upward, a sensation ingrained in me from childhood. Here, the horizon stretches infinitely, seamlessly connecting everything in its view. This experience led me to think about the idea of a "common landscape"—my hope that all women, regardless of their backgrounds, can connect through shared experiences and identities, much like the desire Adrienne Rich expresses in The Dream of a Common Language. In this context, I dream not just of a common language, but a common landscape, where the horizontal gaze becomes a metaphor for unity, equality, and shared vision. The verticality of Korean culture, rooted in its mountainous geography, contrasts sharply with the horizontal gaze I now experience. This horizontal view invites me to imagine a world of equality, where boundaries are less rigid—though I still feel something is missing, as this vision remains incomplete.

This horizontal gaze resonates deeply with me in my art practice. It represents my longing for a more interconnected and equal world, and it influences not just the physical layout of my paintings, but also how I conceive of the narratives and elements within my work. Yet, I find myself yearning for the vertical gaze as well. Even as I encounter the horizontal land, there is still something missing. These two perspectives must interrogate and engage with each other. On canvas, I aim to integrate both horizontal and vertical compositional approaches, allowing their interplay to reflect the duality of my experience. The horizontal gaze transcends limitations, offering freedom and possibility, while the vertical evokes a sense of groundedness, tradition, and aspiration.

I am also reminded of my favorite painter, Amy Sillman, whose work has had a profound influence on me. Sillman, influenced by Japanese calligraphy, frequently discusses the role of calligraphy in her drawings. Like Sillman, I integrate elements of calligraphy into my art to connect with my cultural heritage. Her reflections on how mark-making and drawing are intertwined with personal identity inspire me to consider how my own artistic practice bridges my personal history with broader, universal themes.

While my reflections on the vertical and horizontal gaze are deeply personal, they also offer broader resonance for others navigating cultural dualities or diasporic experiences. The themes of longing for what is lost, yearning for unity, and the tension between rootedness and expansiveness are universal. Many people experience these conflicts, whether through the movement between cultures or through personal reflections on their own lives. My work speaks to this shared human experience—of reconciling personal histories and identities with the desire to imagine and create a more egalitarian, connected world.

As someone born and raised in South Korea, I’ve always felt an inexplicable longing when looking at vertical landscapes in art, a sentiment deeply tied to the geographical relationship between north and south on the Korean peninsula.

My family name, Pungcheon Im clan (任), originates from the Pungcheon area in South Hwanghae Province, which is now part of North Korea. During the Japanese colonial period, my grandparents relocated to a remote region in South Korea to escape the turmoil of war. They settled in Chungcheongbuk-do, an inland area that was considered relatively safe. This region, lacking ports or major military roads, was not a strategic site for battles or large-scale military operations, making it a haven for many seeking refuge.

Unlike many families separated by war, my grandparents were fortunate to keep their family intact. However, they lived under Japanese rule for decades, during which they were forced to adopt Japanese names and suppress their Korean identity. Even now, both my grandparents can speak Japanese fluently, a testament to the lasting impact of that era.

I recall a moment from my childhood when my grandfather asked me to fetch something from the kitchen. His request was peppered with Japanese words—scissors, cup, knives, floor—and I struggled to understand him. Despite this linguistic legacy, my grandparents often reminded me and my brother Subin never to marry a Japanese spouse. My grandfather would firmly say, “You can marry someone of any color, but not Japanese or bbalgangyi (a term for communists).”

My grandfather, proud of our family’s lineage, would often spread out our family jokbo (genealogy record) and recount stories of our ancestors. He spoke of the family’s origins in China, their migration to the north, and their eventual contributions to Korean history. While I rarely paid full attention to these stories, I loved the idea that our family were immigrants. To my younger self, being a mix of cultural roots felt far more fascinating than being “original.”

This mix of pride in our roots and the scars of history left my grandparents with a dual legacy: a deep resentment toward Japan and a profound yearning for the northern land. This longing for the north, where our family originated, seems to have influenced me too. I’ve always felt drawn to the idea of going “up” rather than “sideways” — toward the place where our roots began. A land that exists just above me, yet remains forever out of reach.

This sense of longing extends to my art. Traditional Korean paintings often favor vertical compositions over horizontal ones, a reflection of Korea’s mountainous geography, where 70% of the land consists of mountains and hills. When I’m in Korea, most of the photos I take are vertical. The landscapes stretch upwards, small but reaching for the sky. Perhaps unconsciously, I find myself naturally expressing this verticality in my strokes when I paint. My body gravitates toward vertical compositions, as if responding to an ingrained longing for upward motion.

This tendency also stems from my calligraphy (seoye) practice, which I began alongside my grandfather. Traditional Korean calligraphy is written vertically, a format that mirrors the way most Korean books and journals were written before modernization. My grandfather, with his meticulous brushstrokes, instilled in me a deep appreciation for this vertical flow. Practicing calligraphy with him was more than an artistic exercise; it was an embodied connection to our shared history and a reminder of how deeply verticality is rooted in Korean culture.

If painting originates from the body, then before the body moves, there is the gaze. The gaze carries a horizontal flow — a connection, a continuity. It moves beyond the confines of the canvas, creating an expansive sense of freedom within the frame’s limitations. Traditional Korean painting formats like folding books (hwachup) or folding screens (byungpung) allow the gaze to flow endlessly. These extended formats contrast with the personal, intimate narratives embedded in my vertical strokes, creating a dialogue between the horizontal and vertical in my work.

Through this interplay, I realize that my artistic practice is deeply tied to both physical and emotional landscapes. The vertical strokes carry a sense of personal longing, while the horizontal flow offers a sense of liberation. Together, they reflect the tension between rootedness and expansiveness, between longing for what is lost and embracing the freedom to imagine.

〰️

〰️

Sugar Sugar Rune

In 2018, I began to sense that contemporary love ideology was becoming highly commoditised. I started drawing heart emojis, and one day during a phone call with a close friend, the topic of the Japanese manga ‘Sugar Sugar Rune’ came up. My friend (@ahnnewjin), a fellow BFA graduate and such a talented creative art historian who actually paints, and I was talking to her why I had drawn to making heart-shaped origami out of the blue - even though I was origami geek when I was a child. We began to question what love meant to us, especially as those who remembered the pre-internet era, and how that meaning had evolved over time.

(I also did fold up my canvas to make heart-shaped origami too)

The Representation of Love in Anime

We recalled all the Japanese animations - Full Moon (満月をさがして), Magic Knight Rayearth (魔法騎士レイアース), Magical DoReMi (おジャ魔女どれみ), Inuyasha (犬夜叉), Cardcaptor Sakura (カードキャプターさくら), Sailor Moon (美少女戦士セーラームーン), Wedding Peach (愛天使伝説ウェディングピーチ) - we had been captivated by as young girls, questioning what love had looked like back then and how it had changed over the years. The female protagonists in these animations often embodied moral values, helping others as princesses or sorceresses, yet they still faced tragic and unfulfilled loves, often losing themselves in these conflicts. These characters became objectified yet were expected to embody multiple roles simultaneously.

As part of the generation of Koreans born in the '90s, we grew up watching these portrayals of love. I began to obsessively collect heart images from these animations, which presented love in the form of soft, jewel-like shapes. Yet, in many of these stories, there is always a dark antagonist—a black heart, which is portrayed as even more powerful than any other heart. (Sugar Sugar Rune presents love as a magical spell and monetary unit divided by colors and prices. Each color symbolizes a different meaning and value of love, creating a layered portrayal of love's commodification.)

These are the original heart images from Sugar Sugar Rune including meanings and price

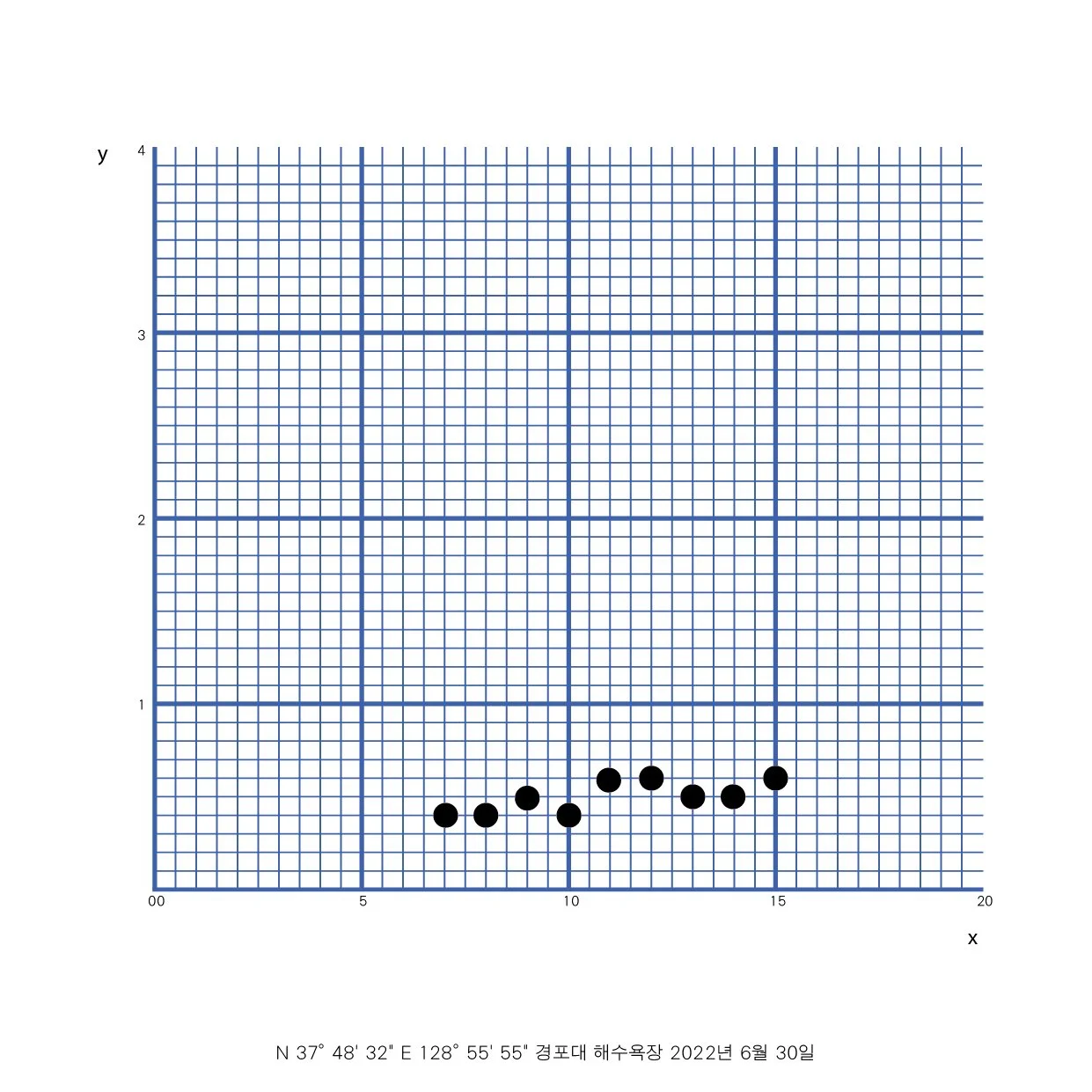

Data-driven Images of Love

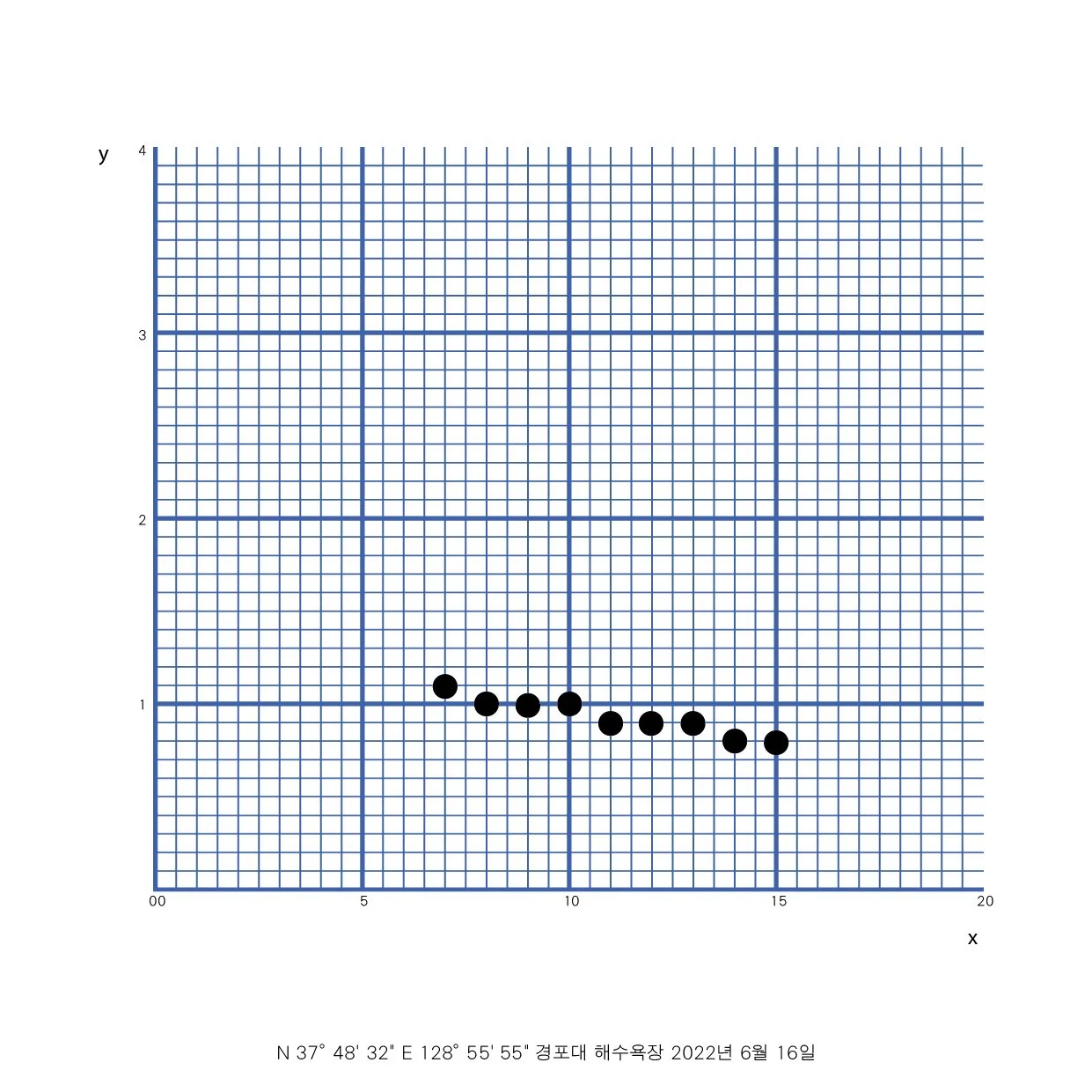

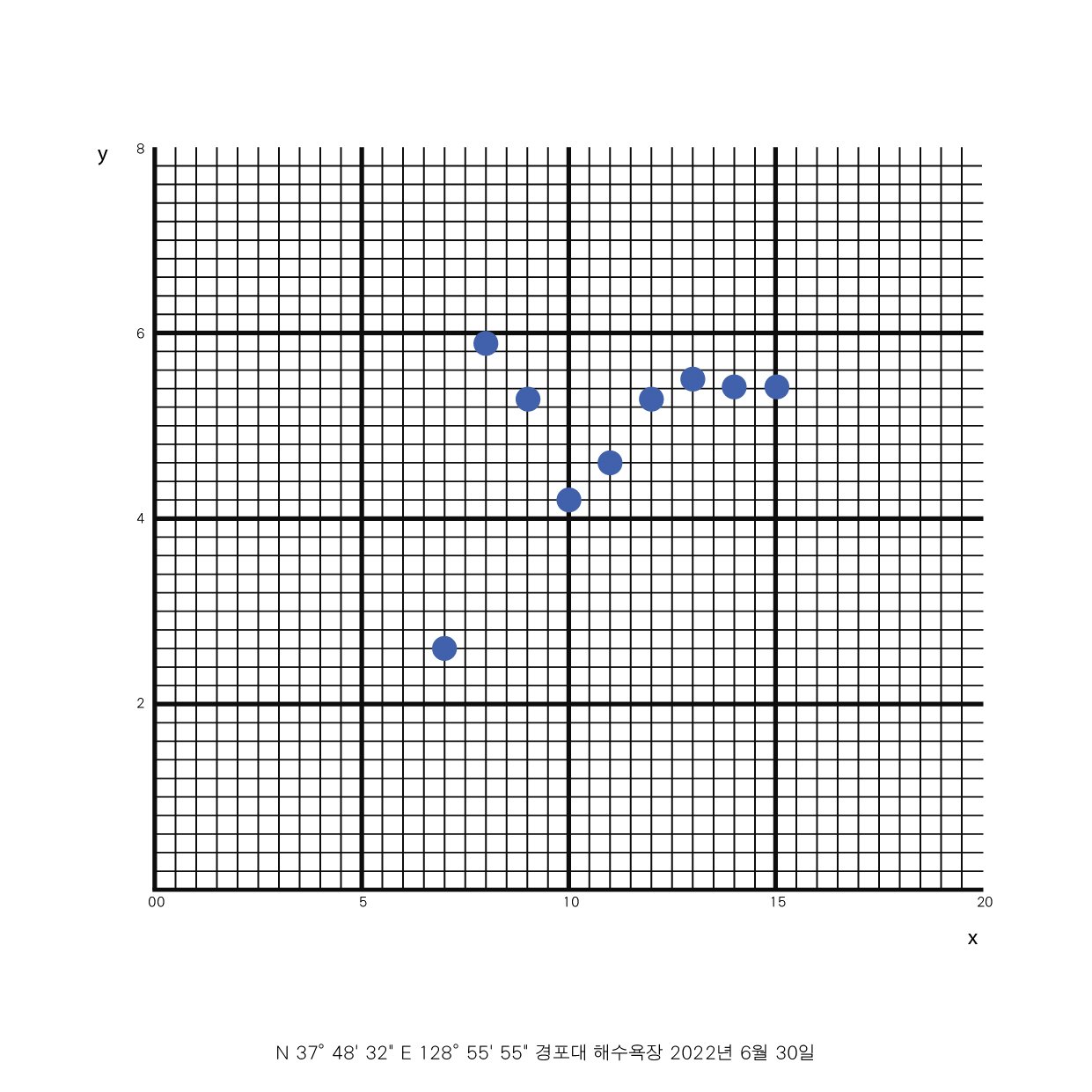

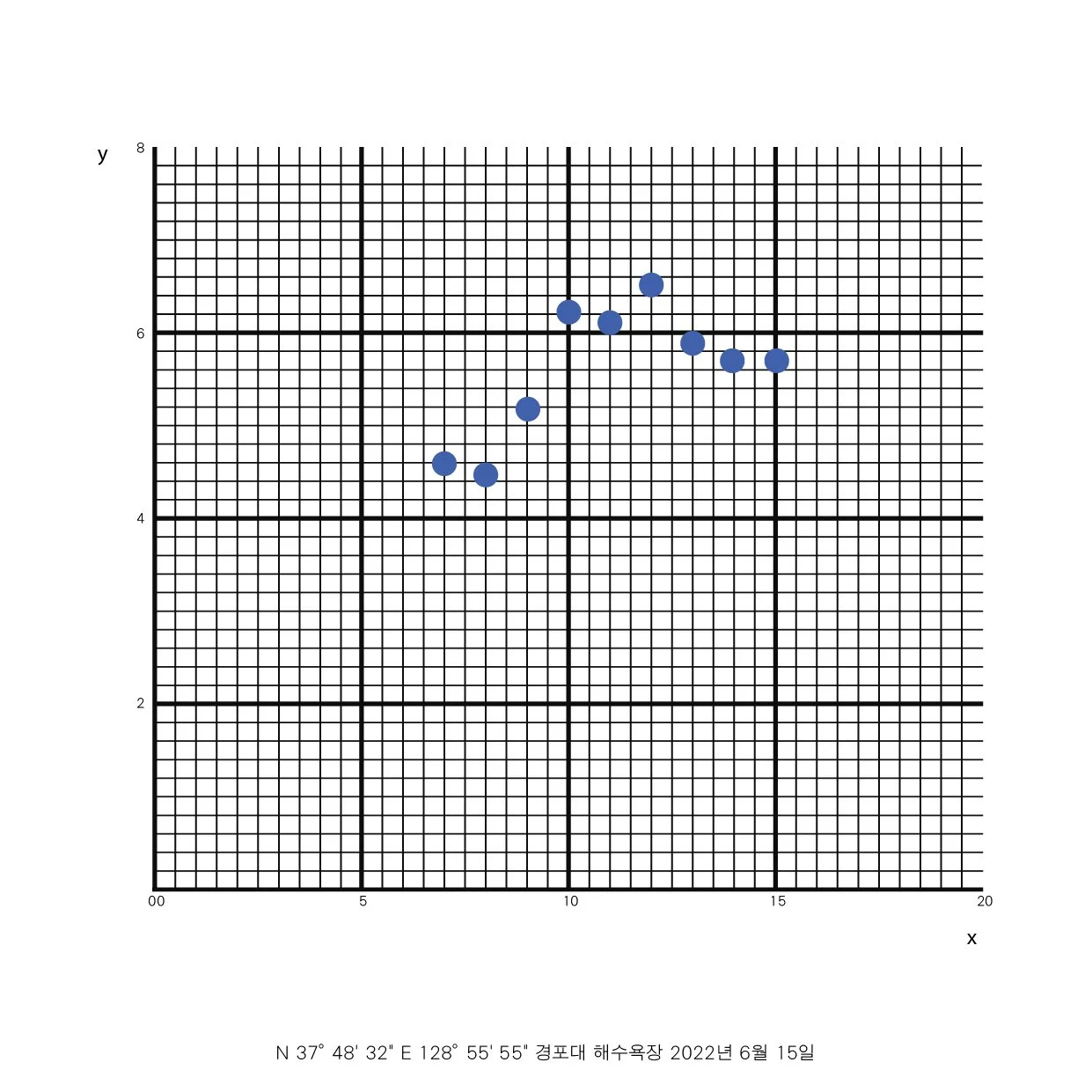

Using Python and OpenCV, I visualized the RGB values of each collected heart image, creating abstract, data-driven representations of hearts with unique and subjective meanings. These hearts, while initially possessing different colors and meanings of love, were reduced to patterns of numerical data, symbolizing the irony that modern love ideology often reduces emotions to mere symbols or images without substance. It raised the question: are we truly experiencing love, or merely consuming its commodified symbols?

The Collision of Love and Society for Korean Women

As I grew older, I found that my understanding of love was evolving, yet many women, myself included, struggled to break free from the ideologies surrounding it. I experienced the impact of these societal constructs firsthand through my first marriage, encountering the intense expectations and limitations that Korean women face. Women who openly confront their realities or question societal norms are often stigmatized as mentally unwell. This societal “witch hunt” persists even in 2024, silencing countless women who decide that remaining quiet is the only way to avoid being labeled as “crazy.”

In Korea, these accusations often take the form of weaponized mental health diagnoses. Right before and after my divorce, exactly four men told me that I “had a mental illness.” One of them, perhaps predictably, insisted that I get tested for OCD, which led me to visit a psychoanalyst. Of course, two psychiatrists later confirmed that these accusations were nothing more than a form of manipulation. This experience taught me that confronting uncomfortable truths often provokes fear in others. As someone who speaks what I see, plainly and without restraint, I inevitably ask questions that are sharp and bold. But for those who cannot face the truth, the easiest way to extinguish the flame of such questions is to discredit the questioner. “You’re mentally ill,” they say, attempting to erase both the question and its source.

Asian women, in particular, are acutely vulnerable to this. Societal expectations—both in Korea and abroad—often push us into silence, forcing us to conform rather than risk being labeled “mad.” These pressures are compounded by the racial and gender stereotypes we face in Western contexts, where hypersexualization and assumptions about submission create an additional layer of discrimination.

But I refuse to hide or feel ashamed of my reality simply because it may seem distant from the norm. To question one’s reality, even when it diverges from societal norms, is perhaps one of the most fundamental human tasks. I embrace this divergence because it holds significance. I am an extraordinary person in Korean society, and while I know there are others who pursue such a path, I also recognize the pain it can bring. Yet this pain is not without value—it is part of the ongoing struggle to define ourselves beyond societal limitations.

Conclusion

Through this journey, grappling with love and societal expectations, I have come to a deeper understanding of love and its evolving nature in modern society. Though love may constantly change, the questions it raises remain persistent. What is love, and how should it be defined?

Contemporary love may be more than a commodified image—it may be a value we must continuously reclaim, redefine, and protect, even in the face of discomfort and resistance.

Sugar Sugar Rune, 2022, Open CV

Am I Really Me?

‘Self Portrait’, Exhibition photo from GIAF (Gangneung International Art Festival) 22.11.04 - 12.04, Photographer Kim, Yo-han (@koreaimg)

‘Self Portrait, digital self’

This happened in 2020, and I created these pieces in 2022-2023.

I fractured into the digital world. My scattered face resembles the reflection I see in the mirror. My face was the only evidence of my existence during the COVID era. In my experience, painters paint their own face because they struggle with their lacking existence in the world. They should see themselves in the canvas. I can’t recall what my facial expression was back then. I didn’t hear my heartbeat because I simply didn’t pay attention in my actual body but a digital one. I painted my self portrait painting because it happened to be waving.

Leaving my wavering self behind, I was focused on creating a performance instead. I wore my Apple Watch on my wrist while painting, drawing, working out and sleeping. My paintings became digital images, and my movements were also translated into the digital realm. The images were predominantly pixelated because I relied on my Instagram account to showcase my work. At times, I thought it was pretty cool. I sold my pieces through Instagram, which brought me a larger audience for a while. However, I eventually realized that this intangible fame was an odd trade-off between the easy rewards of synapses firing in my brain and the compromised quality of my work. I was pleased to receive some feedback, but it didn’t truly affect my artistic practice.

Even before I questioned this system, I found a great sublimation—perhaps I should call it self-distraction—in activities like surfing, body obsession, health obsession, and capturing Instagrammable moments to feel a sense of connection with the world. Now, though, it seems like many people developed a misguided relationship with social media during the COVID period. I connected my body to digital wearable technology. I constantly DMed others and reacted to their stories. My watch tracked my surfing sessions from morning to evening, monitored how many calories I burned at the gym, and even recorded how long I spent having fun at the nightclub.

I felt an urgent need to track every workout, fearing I might miss out on capturing captivating images, visiting inspiring places, or attending exhibitions during the isolation of COVID. While many struggled to pursue their passions during that turbulent time, I found myself navigating a virtual lifestyle, trying to connect in a world that felt increasingly disconnected. I found myself and others within this digital record. All the reactions I received made it seem like everything was okay.

I surfed with my wearable watch, and went, “Oh, I am(or was) here.” I felt relieved, and this digital connection enriched my otherwise mediocre artistic life. It helped me pinpoint where I was. I’ve never been physically inexistent. And even though this digital world made me feel very much existential I still felt impossibly inexistent. Perhaps what I wanted to heard from this machine was:

“I see you.”

I saw myself reflected through them. Maybe it’s more accurate to say, “I see my tracking, so I know I am working hard and doing something. This world looks doomed. Everything feels daunting. But look at me! I’m trying to connect with my body. I am moving. I am alive! This data record shows that.”

Yet I question myself: Was that really me? Was I there? The GPS data, live wave data, and heart rate data made me feel like I existed somewhere for sure. But is it really what you want to see? No. It was merely data. So I stopped using all the applications and social media.

It’s not just my face. I painted my face while imagining surfing in the ocean and cut the painting into pieces to create a graph. I made the wave data charts with my face and marked the actual wave data recorded by my smartwatch. It is my face. A fractured face. But still, I don’t know if it truly is my face.

I didn't realised that this picture would be the last photo that featuring all three self-portraits at that time. My photographer friend Yong-soo Sim (@yongsoosim) visited my studio and this has taken for another reason.

Gestures

There were wanderers who walked following the stars. At first, there was their conversation. From that conversation, gestures began to accumulate. Gestures became diverse, continuously speaking, writing, drawing, making, singing and dancing. Thus, scattered gestures, following the stars dotted in the sky, began to take place within a single space and time. Countless stars became a particular point, then they were interconnected, intertwined, and crossed each other repeatedly. Thus, the products of chance, repeatedly creating new shapes, became constellations.

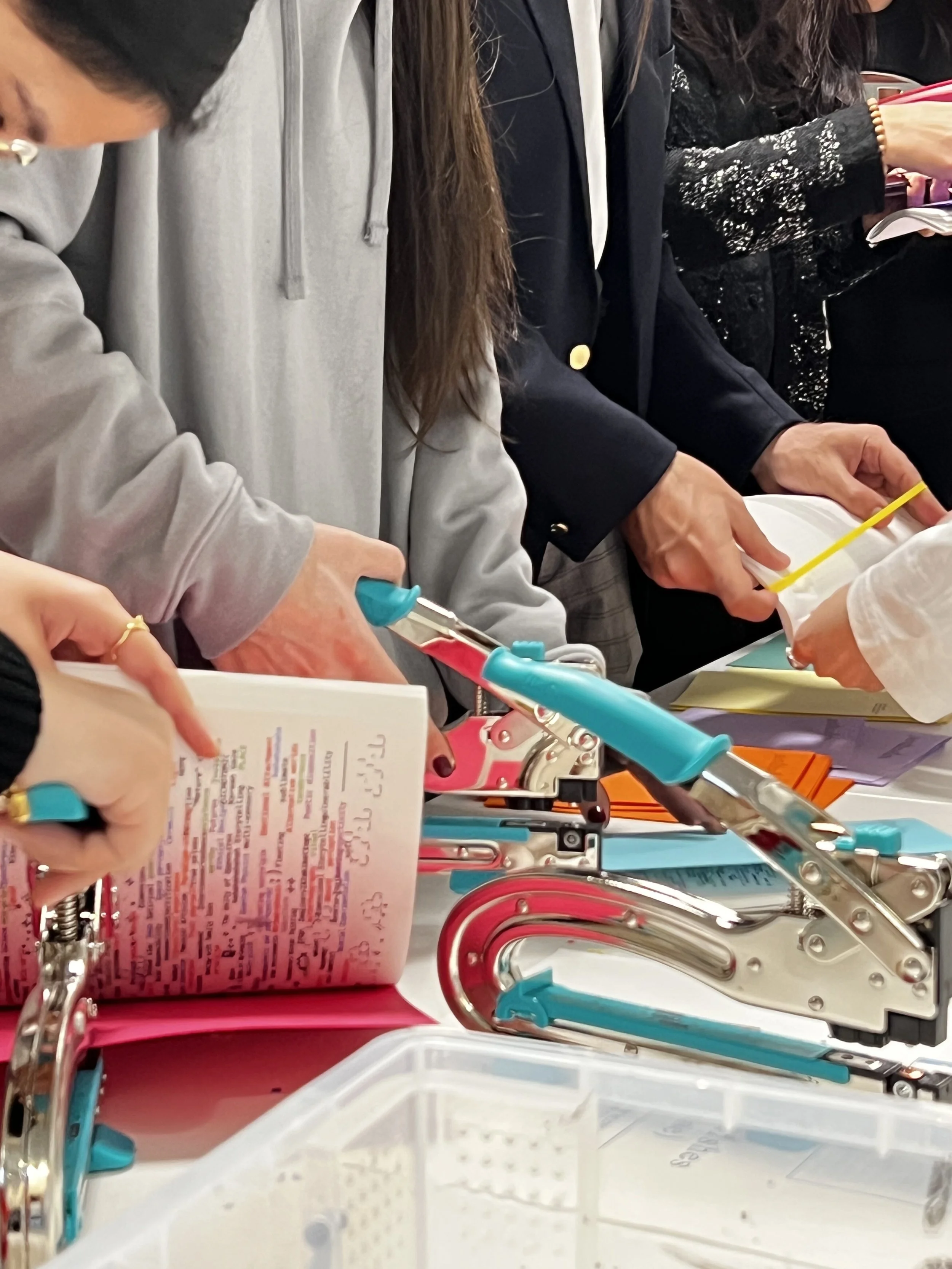

Just as Vilem Flusser said, the gesture of writing is a penetrating gesture. Through the Graduate Diploma course, we began to engrave our own dots. Those dots would be positioned in similar places at a similar time both virtually and physically. Then the points embark on a journey from the particular, soon becoming constellations.

The gestures of every September 2023 Grad Dip wanderer are perforated within these pages. I know this inscribed surface has already engraved each other's minds, never to fade away.